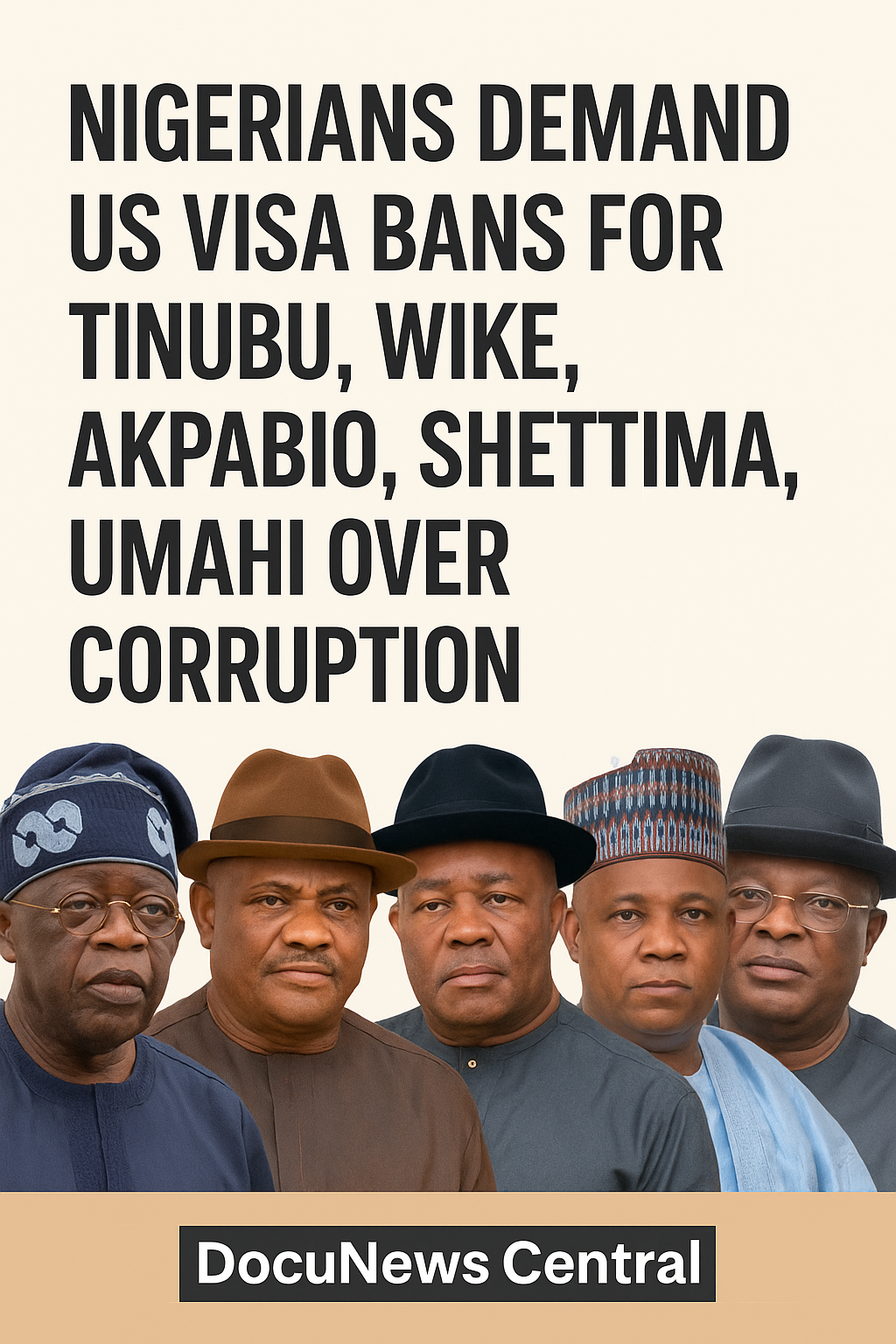

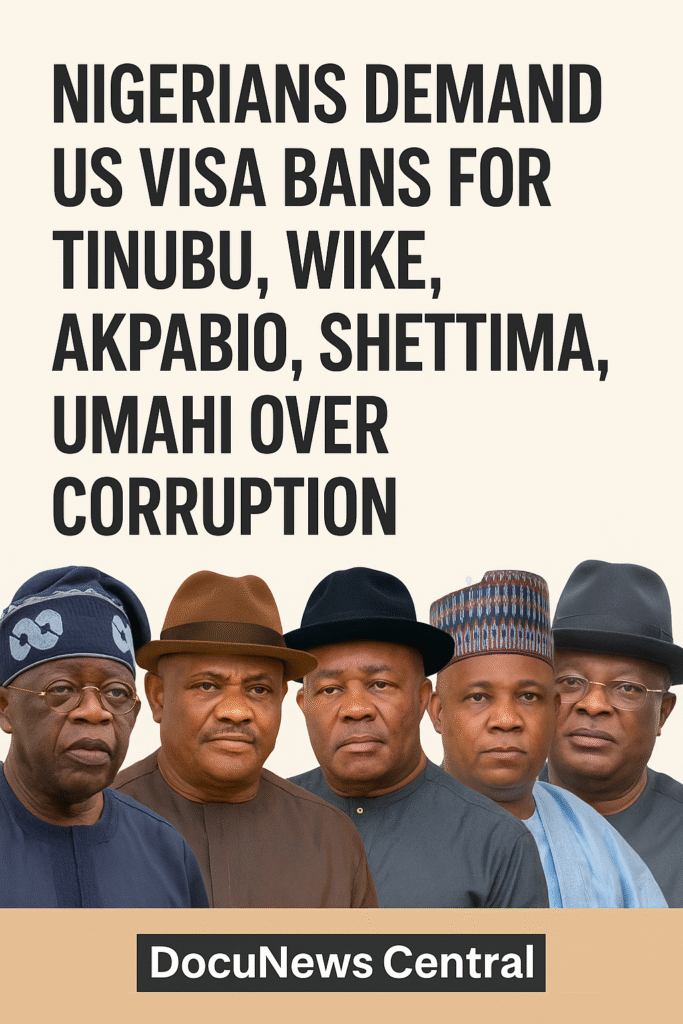

In recent weeks, a growing chorus of voices across Nigeria has called upon the United States to impose visa bans on a number of prominent Nigerian political figures—including Bola Tinubu, Nyesom Wike, Godswill Akpabio, Kashim Shettima, and Dave Umahi—on grounds of alleged corruption. The demand reflects deep frustration among citizens, civil society and media with what they perceive as a persistent culture of impunity among the nation’s political elite.

This blog examines the context, the arguments, the stakes, and possible outcomes of this demand—why Nigerians are calling for it, how the U.S. has responded, what it signals for Nigeria’s governance, and what risks and opportunities lie ahead.

1. The Context: Corruption and Governance in Nigeria

Nigeria has long grappled with the challenge of corruption. From embezzlement of public funds, patronage networks, vote-buying, to public procurement abuses, the phenomenon crosses all levels of government. The effect: eroded trust in institutions, weak service delivery, stunted economic growth, and deepening inequality.

Recent reports from international bodies underline the scale of the problem. As one article putting it, “corruption remains embedded in Nigeria’s institutions”.

In this environment, citizens often feel powerless: the people believed to be accountable often appear protected by political networks, and sanctions are rare or ineffective. It is against this backdrop that the demands for external accountability mechanisms—including foreign visa bans—have gained traction.

2. The Call: Who, What and Why

Who is being targeted?

The demands focus on high-profile individuals:

- Bola Tinubu — former Governor of Lagos State, now President of Nigeria.

- Nyesom Wike — former Governor of Rivers State and key political actor.

- Godswill Akpabio — prominent politician from Akwa Ibom, former Governor and Senate President.

- Kashim Shettima — from Borno State, former Governor, now Vice-President.

- Dave Umahi — from Ebonyi State, former Governor, now Minister.

These names are representative of the power elite in Nigeria: they hold or have held significant offices, commanding both political and economic resources.

What are they asking for?

Simply put: that the U.S. government deny visas or otherwise block entry into the U.S. for these individuals (and potentially others) on the basis of alleged corruption. The idea is that a visa ban would act as a deterrent, a form of external accountability when domestic mechanisms seem weak.

Why is this being demanded now?

Several inter-related reasons:

- A sense of frustration that domestic anti-corruption institutions (such as the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) ) have not delivered decisive results at the highest level.

- Growing awareness that Nigeria’s image abroad is tarnished, and that corruption has real costs (investor confidence, growth, debt burden).

- Public outrage that while ordinary citizens suffer economic hardship, the political class appears to enjoy privileges, sometimes including foreign travel, while facing little consequence.

- The U.S. messaging itself: the United States Mission in Nigeria recently reaffirmed that “high-profile individuals who engage in corruption can be barred from receiving U.S. visas.”

- Civil society activism: petitions and media campaigns have sharpened the focus, making this a visible demand beyond just social media.

3. The U.S. Position — What Has Been Said

The United States has, via its mission in Nigeria, made statements that signal willingness to use visa restrictions as part of its anti-corruption toolkit. Notably:

A statement on 23 September 2025 from the U.S. Mission in Nigeria noted, “Fighting corruption knows no borders or limits on accountability. Even when high-profile individuals engage in corruption, they can be barred from receiving U.S. visas.”

Another news report summarised: “US threatens visa ban for corrupt Nigerian officials.”

However, fact-checking organisations point out that the U.S. does not publish specific names of visa-banned individuals, and the records are confidential.

Thus, while the policy environment suggests the possibility, there is no publicly confirmed list of individuals from Nigeria who have already been banned for corruption (as distinct from e.g. election-related abuses).

4. The Arguments For & Against

Arguments in favour

- Deterrence: If prominent political actors know foreign travel could be restricted, they may think twice about engaging in corruption.

- External accountability: When domestic systems are weak, foreign visa bans act as a complementary mechanism.

- Symbolic value: It sends a message to citizens—and to the world—that Nigeria’s elite are not entirely beyond reach of consequences.

- Alignment with global norms: Many countries now use sanctions or visa restrictions in anti-corruption efforts; Nigeria-U.S. relationship should reflect that.

- Moral imperative: Public funds belong to the people, not the few; if those in power betray that trust, foreign governments may be justified in restricting privileges.

Arguments against / challenges

- Sovereignty concerns: Critics argue that foreign governments imposing visa bans on domestic political actors can be seen as external interference.

- Domestic legitimacy: Some may interpret visa bans as politically motivated or as favouring certain factions; this could deepen divisions.

- Selective enforcement risk: If only some individuals are targeted, suspicion may arise that bans are being used as political tools rather than based on impartial criteria.

- Effectiveness: A visa ban alone may not stop corruption; the root causes (weak institutions, low salaries, patronage culture) remain.

- Diplomatic relations: Nigeria–U.S. ties could be strained; the Nigerian government may push back hard if perceived as being shamed or coerced.

- Due process / transparency: Because visa decisions are confidential under U.S. law, affected individuals cannot easily contest or publicly defend themselves, which raises fairness concerns.

5. Why These Five Names?

The selection of Tinubu, Wike, Akpabio, Shettima and Umahi is significant for several reasons:

- They occupy or have occupied senior political offices—governors, ministers, national leaders—thus increasing the stakes of accountability.

- They represent diverse regions of Nigeria (South West, South South, South East, North East), indicating the demand is not region-bound but national.

- They are political kingmakers and part of Nigeria’s ruling network; targeting them symbolises a demand to hold elite power to account.

- Their offices, past and present, have been the subject of allegations of misuse of funds, patronage and governance deficits (though each also has defenders).

While the demand does not imply that all five have been legally convicted of high-level corruption, the calls underscore public perception that their accountability should be scrutinised in a way commensurate with their positions.

6. What Would It Take for a Visa Ban to Be Imposed?

For the U.S. to impose a visa ban on a specific individual for corruption, a number of conditions generally must be met:

- A credible evidence trail linking the individual to corrupt acts (misappropriation, bribery, embezzlement), or an official finding of wrongdoing.

- Internal U.S. inter-agency review (Department of State, Treasury, Justice) under relevant laws and policies.

- Application of sanctions or visa restrictions must align with U.S. law (for example, sections of the Immigration & Nationality Act, or the Global Magnitsky Act).

- Coordination with U.S. Mission abroad (in this case, Nigeria) and consistency with foreign-policy objectives.

- Consideration of diplomatic implications (impact on Nigeria-U.S. relations, stability).

Given this process—and the fact that visas are confidential—the absence of a published list does not mean the U.S. is not acting in specific cases. But it does mean transparency to the Nigerian public is limited. This lack of transparency can feed both scepticism and speculation.

7. Potential Impacts on Nigeria

Positive impacts

- Strengthening institutional morale: If the public sees external consequences for corruption, it may revitalize domestic agencies like the EFCC or the Independent Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Commission (ICPC).

- Behavioural change: Political actors may become more cautious, reducing corruption-enabling behaviours, even if indirectly.

- Improved investor confidence: Foreign investors may view Nigeria more favourably if it appears committed to cleaning up its governance environment.

- Empowerment of civil society: Activists and watchdog groups may feel emboldened when they see their demands gaining traction on an international stage.

Risks / unintended consequences

- Political backlash: The Nigerian government could retaliate, perhaps by restricting U.S. access, lobbying harder for diplomatic immunity for officials, or publicly denouncing the U.S. stance.

- Perception of external interference: Some Nigerians may view visa bans as foreign meddling, feeding narratives of neo-colonialism or external coercion.

- Domestic displacement: If foreign travel is restricted, affected individuals may shift to less-monitored domains, making corruption less visible but not less real.

- Public disillusionment: If visa bans are announced but no follow-through domestic reforms happen, the public may become cynical—“nothing changes for us, only they lose privileges”.

- Selective immunity: If only opposition or certain figures are targeted, while allies are spared, the policy may be perceived as biased—thus undermining its legitimacy.

8. What the Nigerian Government Might Do

In response to this growing demand and to the U.S. messaging, the Nigerian government has several options:

- Pre-emptive reforms: Launch high-level anti-corruption investigations, public prosecutions, official asset-recovery efforts, thereby demonstrating domestic commitment.

- Public diplomacy: Engage with the U.S. diplomatically to clarify Nigeria’s position, perhaps negotiate frameworks for cooperation on transparency and visa policy.

- Institutional strengthening: Empower agencies like the EFCC and ICPC, ensure independence, publicise results (especially convictions) to show the world reform is underway.

- Domestic narrative-building: Shift the narrative from external pressure to national ownership: e.g., “Nigerians demand accountability, the U.S. stance validates our efforts”.

- Risk-management: For the individuals named (or others), take steps to avoid travel to the U.S., or ensure their presence does not trigger visa refusals and diplomatic incidents.

9. The Role of Nigerian Civil Society and Media

Much of the momentum behind the visa-ban demand comes from civil society organisations, NGOs, the press and online advocacy. Their roles include:

- Researching and documenting alleged corruption cases, asset trails, procurement irregularities.

- Mobilising public opinion: petitions, social media campaigns, demonstrations.

- Holding the government to account: demanding transparency on what the EFCC/ICPC are doing, pushing for prosecutions.

- Engaging international institutions: asking the U.S., UK, EU to consider visa/sanction options; collaborating with anti-corruption networks abroad.

- Educating citizens: explaining how corruption affects everyday life—education, health, infrastructure—and why accountability matters.

In doing so, they help turn what might otherwise be niche policy discussion into a broad-based public demand.

10. What It Means for the Politicians Named

For the specific individuals – Tinubu, Wike, Akpabio, Shettima, Umahi – the calls for visa bans carry several implications:

- Their international mobility may be impaired (or risk being impaired) – which for high-level politicians often matters (travel, business interests, global networking).

- They may face increased scrutiny, both domestically and internationally: media may dig deeper into their public records, asset disclosures, procurement decisions.

- They may face political ramifications: opposition forces may use the visa-ban demand to portray them as corrupt and unfit for office, thereby influencing public opinion or intra-party dynamics.

- They may choose to pre-emptively defend themselves, issuing statements, commissioning audits, or threaten legal action if they perceive the demands as defamatory.

- Even if no ban is ultimately imposed, the reputational cost may be real: to be publicly named as under consideration for visa ban for corruption is a badge of dishonour in political optics.

11. Broader Lessons for Nigeria’s Governance

This episode – the demand for U.S. visa bans – offers broader lessons about governance in Nigeria:

- Accountability isn’t just domestic: In an interconnected world, domestic failures may trigger external consequences.

- Perception matters: The fact that many Nigerians feel corruption is entrenched feeds instability; restoring trust is essential.

- Institutional reform is long-term: Visa bans alone won’t solve corruption; strengthening institutions, enforcing laws, improving transparency and civic education matter.

- Public participation counts: The pressure for visa bans emerges because citizens and civil society refuse to be silent; democratic culture depends on this.

- International relations are two-way: Nigeria must engage respectfully with partners like the U.S., but also assert its own agency and forbear being treated purely as recipient of foreign pressure.

- Leadership example is key: When top officials are seen to act with probity, the cascade effect on the entire system can be profound.

12. What Next? Scenarios

Here are possible scenarios of how this demand (and the broader visa-ban policy) could unfold:

- Scenario A – U.S. imposes targeted bans

The U.S. identifies one or more Nigerian individuals – possibly from the list named – for alleged corruption, and announces visa restrictions. The Nigerian government protests diplomatically, but also uses the incident to push for domestic anti-corruption action. Civil society gets a boost. The message to Nigeria’s elite: there are real external consequences. - Scenario B – U.S. sends warning but no named bans

The U.S. continues to signal that corrupt Nigerian officials risk visa restrictions but does not publicly name anyone. The effect is ambiguous: Nigerian officials may feel pressure but also uncertainty. The call for visa bans by Nigerians continues, while domestic politics remains largely unchanged. - Scenario C – Nigeria rejects the pressure

The Nigerian government denounces external visa-ban pressure as interference, downplays the issue, and refuses to accelerate reforms. Civil society becomes more adversarial; public trust declines further. Foreign investors and partners may become more cautious, leading to economic consequences. - Scenario D – Domestic reform overtakes external pressure

Reacting to the visa-ban demand and U.S. messaging, Nigeria accelerates anti-corruption reforms: high-profile investigations, prosecutions, asset recoveries. The visa-ban narrative becomes less relevant because the system begins to deliver. That’s the most positive outcome for citizens.

13. My Take: Why the Demand Matters

From my perspective, the demand for U.S. visa bans is symbolically important and pragmatically useful, but it is not a silver bullet. Here’s why:

Symbolically: For too long, the perception in Nigeria has been that “the big man” can act with impunity. A credible threat of visa ban pierces that perception. It says: you are not beyond consequences.

Pragmatically: It creates an additional lever of accountability. Domestic agencies may feel compelled to act (or risk being seen as failing while external sanctions loom).

But: It must be coupled with domestic action. Without visible prosecutions and institutional reform, the visa-ban threat risks being seen as external theatre. Worse, if applied selectively or politically, it could backfire.

Additionally: The Nigerian public must be educated that visa bans are one tool among many; they do not replace the need for strong courts, independent watchdogs, transparent procurement, citizen oversight.

In short: the call for visa bans is a symptom of the frustration Nigerians feel with governance, and a strategy to try to force change — but ultimately real change must be driven at home.

14. What Nigerians Should Be Watching

As this issue evolves, Nigerians — and especially civil society and media — should pay attention to several signals:

- Which names emerge publicly: If one of the five (or others) is publicly named by the U.S. for visa restrictions, that is a major turning point.

- Domestic anti-corruption outcomes: Are there new prosecutions, asset recoveries, high-level accountability actions?

- Response from Nigerian government: Will the presidency or National Assembly engage in reform, diplomatic push-back, or ignore the issue?

- Civil society momentum: Are petitions, protests, media investigations escalating? Do they influence policy?

- Investor and donor reactions: If foreign investors, multilateral banks, donor agencies begin citing corruption risk in Nigeria in response, it amplifies the pressure.

- Public opinion shifts: Are ordinary Nigerians starting to believe that the elite can be held accountable? That behaviour will change?

- U.S.–Nigeria diplomatic dynamics: Does this become a bilateral flash-point? Or is it handled quietly?

15. Conclusion: A Moment of Opportunity

This moment – the demand for U.S. visa bans for high-profile Nigerian politicians – is not merely about travel privileges or foreign policy theatre. It is about accountability, governance, citizenship and trust. When Nigerians demand that figures like Tinubu, Wike, Akpabio, Shettima and Umahi be barred from entering the U.S. over corruption, they are saying: we will no longer accept a system where the powerful escape consequence.

For the U.S., the decision is whether to convert public threats into concrete actions—and if so, to do so transparently and fairly. For Nigeria, the decision is whether to seize this pressure as a prompt—to deepen reform—or to treat it as an external nuisance.

For citizens, the decision is whether to remain engaged, vigilant and persistent—not just hoping for foreign-led action, but also pushing for domestic systems to deliver.

In many ways, this is a moment of opportunity: if handled well, it could mark a shift in how Nigeria’s elite see consequences; if mishandled, it could become another forgotten campaign in a long line of promises unmet.

In sum: Nigerians are demanding more than just visa bans. They’re demanding respect for their rights, the proper use of public funds, stronger institutions, and a country where power isn’t a licence for impunity. Whether the demand for visa bans is the spark that ignites reform—or simply a flashpoint in a longer struggle—remains to be seen. But one thing is clear: the call has been made, the public watching, and the consequences of inaction risk becoming ever more visible.